The Hunter and the Lion, Disputing

Peace had been declared among all people and beasts; no longer did they fight with knife and arrow, nor with tooth and claw. In that time of peace, when a hunter and a lion chanced to meet, they did not fight; instead, they did battle in words, disputing who was stronger of the two. "I'll show you that man is the strongest," said the hunter, leading the lion to a graveyard and pointing to a stone monument placed upon a hunter's tomb; the statue showed a man strangling a lion to death. "Behold," the hunter proclaimed, "how a lion is easily overcome by the strength of a man." The lion only scoffed. "If lions could sculpt as humans do, then you would see a different story," he said, "but until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter."

In retelling this story, I have made it a story of debate; the plot of the story consists of the man showing the lion a statue as proof of human superiority, and the lion then rejecting the man's claim. The dialogue itself is the focus of the fable, as often in Aesop's fables.

There are, however, some versions of the story where the lion counters the man's evidence with evidence of his own. In Caxton's version, for example, the lion refutes the man's argument by fighting with the man and throwing him into a pit:

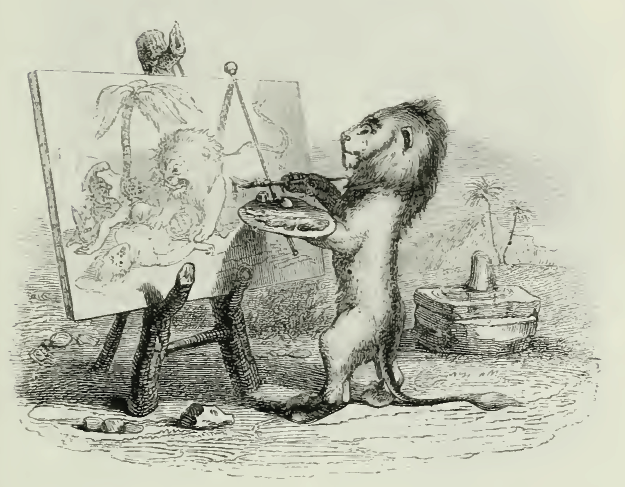

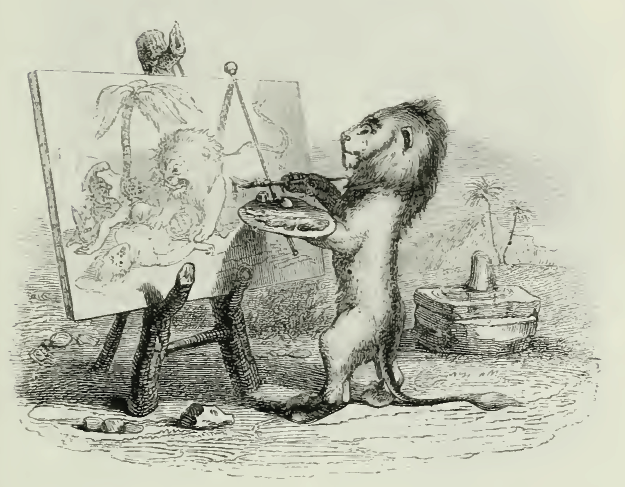

"Cutting stories," as Ogilby says, is about sculpting, but painting is well represented in different versions of the fables, so I'll close with this fine illustration by Grandville for La Fontaine that shows the lion as painter:

Click here for more illustrations and English versions of this fable, and for more "favorite fables" at this blog, see the Aesopica label. You can find out more about this retelling project, see this post: Favorite Aesop's Fables.

Men ought not to byleue the paynture / but the trouthe and the dede / as men may see by this present Fable / Of a man & of a lyon which had stryf to gyder & were in grete discencion for to wete and knowe / whiche of them bothe was more stronger / The man sayd / that he was stronger than the lyon / And for to haue his sayenge veryfyed / he shewed to the lyon a pyctour / where as a man had vyctory ouer a lyon / As the pyctour of Sampson the stronge / Thenne sayd the lyon to the man / yf the lyon coude make pyctour good and trewe / hit had be herin paynted / how the lyon had had vyctorye of the man / but now I shalle shewe to the very and trewe wytnesse therof / The lyon thenne ledde the man to a grete pytte / And there they fought to gyder / But the lyon caste the man in to the pytte / and submytted hym in to his subiection and sayd / Thow man / now knowest thow alle the trouthe / whiche of vs bothe is stronger /And therfore at the werke is knowen the best and most subtyle werker

The fable does include the lion's argument about "if lions could make art," but the story does not stop there: it goes on to set up a contrast between art and reality, so that the moral is about truth as opposed to the lies of art, as the promythium states: "Men ought not to believe the painter, but the truth and the deed." You can see something similar in the medieval Latin version of Ademar where the lion takes the man to an amphitheater where a lion is strangling a man in combat, whereupon he says: "There is no need for the evidence of painting, but for true deeds." This is the direction taken in the medieval Romulus tradition, and hence in Caxton. The fable presumably goes back to Phaedrus; you can read a reconstructed version of Phaedrus by Gudius here.

Note also that Caxton says the artwork depicts Samson victorious over the lion, a Christian parallel to the Greco-Roman tradition that makes the artwork in this fable be Heracles and the lion, as you can see here in Jacobs' version: So he took him into the public gardens and showed him a statue of Hercules overcoming the Lion and tearing his mouth in two. Tenniel actually depicts the man in the fable as Heracles, wearing his famous lion-skin:

The moral of the story in Jacobs, however, is not about art versus truth. Instead, the theme is partiality: everyone tells their story to their own advantage. So, when the lion sees the statue, he rebukes the man with these words: "That is all very well," said the Lion, "but proves nothing, for it was a man who made the statue." The lion does not say that he, as a lion, cannot create art; his focus is instead the partiality of the art presented by the man as evidence.

Other versions also emphasize the idea of partiality. As L'Estrange says in his epimythium, for example: "'Tis against the Rules of Common Justice for Men to be Judges in their Own Case." But even in L'Estrange, there is more at work than partiality in the endomythium, because here is what the lion says: "Well! says the Lyon, if We had been brought up to Painting and Carving, as Your are, where you have One Lyon under the Feet of a Man, you should have had Twenty Men under the Paw of a Lyon." This conceit of the twenty men under the paw of one lion shows up also in James's version.

Hoole's version is like L'Estrange's version in that, within the fable, the lion complains that he is excluded from artistic expression, but in the epimythium, the emphasis is not on exclusion, but partiality: A Lyon wrangleth with an Hunter. He preferreth his own strength beyond a mans strength. After long disputes, the Hunter brings the Lyon to a stately Tomb, wherein a Lyon was engraven, laying his head upon a mans knee. The beast said, that was not evidence enough. For he said, Men engrave what they list: but if Lyons also were crafts-masters, a Man should be engrauen under the Lyons feet. Mor. Every one as far as he can, both saith and doth what he thinketh may advantage his own party and cause.

There are other versions, however, which focus on exclusion in the epimythium as well. For example, here is a version in verse by Boothby, where the moral is about entire nations not allowed to tell their own story.

Lion and Man, on some pretence,Disputed for pre-eminence.In marble wrought, the latter show'dA man who o'er a lion strode."If that be all," the beast replied,A lion on a man astride,You soon assuredly would view,The sculptor's art if lions knew."Each nation would the rest excel,If their own tale allow'd to tell.

One of my favorite versions of this fable is the one by Herford, where he has a very nice idea about just what kind of monument the lion would create:

A Lion and a Man, as theyWere walking in a park one day,Exchanging stories of their strengthAnd deeds of valor, came at lengthUpon the statue of a ManSlaying a Lion. Then beganA wrangle. Said the Man, "I callThat true to nature." "Not at all!"The Lion roared. "You think it trueBecause it shows Man's point of view.If it were mine, the Man would notBe seen!" Exclaimed the other, " What!No Man at all?" "Oh, yes," repliedThe Lion, "he would be inside!"

Herford also did the illustrations. The lion carved by a lion is smiling, with a human bone in his mouth! Presumably the human is, indeed, inside the lion:

This theme of "if the lions could carve" is the theme I wanted to emphasize in my version of the fable, and I included an African proverb, one made famous by the Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe: "Until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter." There are many African proverbs that are like Aesop's fables in miniature; I'll have more to say about that in future posts. It was because of this African proverb that I chose to make the human in my story a hunter; he is usually just characterized as a "man," although in some English versions he is a "forester" or a "huntsman."

For the start of my fable, I was inspired by Ogilby's elaborate poem which describes the peace that, temporarily, reigned among people and animals. Most versions have the man and the lion traveling together for some unknown reason ("The Man and the Lion Traveling Together" is the title in Lloyd Daly's Aesop Without Morals), but I like the idea that this dialogue between the man and the lion carries on the age-old war, but in words this time. Here is the endomythium of Ogilby's poem, where the lion identifies himself as African ("where first I drew my breath"), and champions the African general Hannibal over his perfidious Roman opponents:

Could we, as well as you, our Stories cut,We might, and justly, putYour lying Heads beneathOur Conquering Foot:From partial Pens, all Truth hath been for ever shut.Where first I drew my breath,I heard a Carthaginian at his Death,The Roman Nation most perfidious call;Crying out, by Treason they contriv'd the FallOf them, and their great Captain Hannibal.

"Cutting stories," as Ogilby says, is about sculpting, but painting is well represented in different versions of the fables, so I'll close with this fine illustration by Grandville for La Fontaine that shows the lion as painter:

Click here for more illustrations and English versions of this fable, and for more "favorite fables" at this blog, see the Aesopica label. You can find out more about this retelling project, see this post: Favorite Aesop's Fables.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are limited to Google accounts. You can also email me at laurakgibbs@gmail.com or find me at Twitter, @OnlineCrsLady.