The Carefree Calf and the Hard-Working Ox

A calf went skipping through the pasture when he noticed an ox pulling a plow through a neighboring field. "Poor you," shouted the calf, "working so hard! Look at me, just having a good time!" The ox looked up and snorted. "We'll see." Autumn arrived, and then the farmer adorned the calf with ribbons, garlanded him with flowers, and led him to the harvest festival. Along the way, the calf glimpsed the same ox, let out to pasture for the holiday. "Poor you," shouted the calf, "not invited to the festival. Look at me, all dressed up and going to the temple!" Again, the ox looked up and snorted, "We'll see." Later that day, the ox heard shouts and cheers from the temple, and he smelled the calf roasting on the sacrificial altar. Smiling, he said, "That calf's carefree life has ended in an early death. Given a choice between the yoke on my neck or the axe, I'll take the yoke."

The English names used for the characters in this fable vary: sometimes the hard-working animal is a bull or an ox, and the animal who doesn't work might be a bullock or calf or heifer. For the working animal, I opted for "ox" since that seemed most likely to convey the sense of being a hard worker. The word "heifer" brings in a gender dimension that I didn't want, and the word "bullock" is rarely used, so I went for a calf.

The really challenging part about this fable is the way the animals are supposed to be human exemplars. In the farm world, there are animals raised for slaughter, but that does not apply directly to the human world, so what to do with the contrast between the two animals? I opted to emphasize the difference between someone who works hard and someone who takes the easy way out, thinking they can leave a carefree life without consequences, only to find out they are wrong. I even used the title to set that contrast, and I really like the way "yoke" and "axe" are vivid symbols for the hard-working life, on the one hand, and a sudden, violent death on the other.

I was going to add in the name of the Greek and Roman harvest festival, the Thesmophoria or Cerealia, but pigs were sacrificed at those festivals, not calves, so I did not include that detail, just hoping the word "sacrificial altar" would suggest the ancient context.

It's possible to interpret the contrast in other ways. Some authors apply a class-based reading, with the ox standing for a member of the lower class, and the calf as a frivolous upper-class person. Another approach is to label the calf as being someone rude to a person less fortunate than himself, not realizing that his own fortunes might turn. You can see some examples of these different interpretations below:

Here is James Davies' translation from the Greek fable by Babrias; the yoke/axe contrast goes back to the ancient tradition:

A heifer yet unbroken, roaming free,

A bull hard-work'd in ploughing chanced to see;

And said, "Poor wretch, how grievous is thy toil!"

Nought said the bull, but still upturn'd the soil.

Soon, when the rustics held their solemn feast,

The aged bull to pasture went released;

But ropes that bound its horns the heifer drew,

That it with blood the altar might bedew.

To whom this sentence then the elder spoke:

"'Twas for this end they kept thee from the yoke.

Young before old, thou dost the altar deck;

The axe, and not the yoke, will bruise thy neck."

Godolphin's one-syllable Aesop relies on axe and yoke also: In days of old, a calf that ran wild in some fields near Rome, and had not yet felt the yoke, said to an old ox, "Dull slave! How can you drudge on in this way from day to day with a plough at your tail? Look at me, see how I skip and play!" The ox said not a word, but went on with his work. The next day there was a great feast held at Rome, so the ox did not go to the plough; but his friend the calf was led off in great pomp to be slain, with a wreath round his neck. "If this is the last scene of your gay life," said the ox, "let me drudge on at the plough, for the yoke is more to my mind than the axe. Of two ills, choose the least.

In James, adds a contrast is between work and play in addition to yoke and axe: A Heifer that ran wild in the fields, and had never felt the yoke, upbraided an Ox at plough for submitting to such labor and drudgery. The Ox said nothing, but went on with his work. Not long after, there was a great festival. The Ox got his holiday: but the Heifer was led off to be sacrificed at the altar. "If this be the end of your idleness," said the Ox, "I think that my work is better than your play. I had rather my neck felt the yoke than the axe.'

Here is Tenniel's illustration for James:

L'Estrange's interpretation, not surprisingly, is class-based: A Wanton Heifer that had little else to do then to Frisk up and down in a Meadow, at Ease and Pleasure, came up to a Working Oxe with a Thousand Reproaches in her Mouth; Bless me, says the Heifer, what a Difference there is betwixt your Coat and Condition, and Mine! Why, What a Gall's Nasty Neck have we here! Look ye, Mine's as clean as a Penny, and as smooth as Silk, I warrant ye. 'Tis a Slavish Life to be Yoak'd thus, and in Perpetual Labour. What would you give to be as Free and as Easy now as I am? The Oxe kept These Things in his THought, without One Word in Answer at present; but seeing the Heifer taken up a While after for a Sacrifice: Well Sister, says he, and have not you Frisk'd fair now, when the Ease and Liberty you valu'd your self upon, has brought you to This End? The Moral. 'Tis No New Thing for Men of Liberty and Pleasure to make Sport with the Plain, Honest Servants of their Prince and Country. But Mark the End on't, and while the One Labours in his Duty with a Good Conscience, the Other, like a Beast is but Fatting up for the Shambles. [...] 'Tis the Case of Great and Rich Men in the World; the very Advantages they Glory in, are the Cause of their Ruine.

Croxall's version interprets the calf as someone who has contempt for someone who is in difficult straits, not realizing that he might find himself in difficult straits himself later: A Calf, full of play and wantonness, seeing the Ox at plough, could not forbear insulting him. "What a sorry poor drudge art thou," says he, "to bear that heavy yoke upon your neck, and go all day drawing a plough at your tail, to turn up the ground for your master! But you are a wretched dull slave, and know no better, or else you would not do it. See what a happy life I lead; I go just where I please; sometimes I lie down under the cool shade; sometimes frisk about in the open sunshine; and, when I please, slake my thirst in the clear sweet brook: But you, if you were to perish, have not so much as a little dirty water to refresh you." The Ox, not at all moved with what he said, went quietly and calmly on with his work: and, in the evening, was unyoked and turned loose. Soon after which he saw the Calf taken out of the field, and delivered into the hands of a priest, who immediately led him to the altar, and prepared to sacrifice him. His head was hung round with fillets of flowers, and the fatal knife was just going to be applied to his throat, when the Ox drew near and whispered him to this purpose: "Behold the end of your insolence and arrogance; it was for this only you were suffered to live at all; and pray now, friend, whose condition is best, yours or mine?" MORAL. To insult people in distress is the property of a cruel, indiscreet, and giddy temper; for on the next turn of fortune's wheel, we maybe thrown down to their condition, and they exalted to ours.

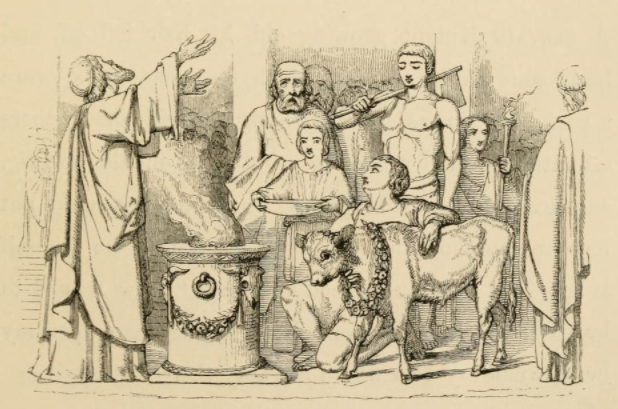

Here is Bewick's illustration for Croxall:

Click here for more illustrations and English versions of this fable, and for more "favorite fables" at this blog, see the Aesopica label. You can find out more about this retelling project, see this post: Favorite Aesop's Fables.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are limited to Google accounts. You can also email me at laurakgibbs@gmail.com or find me at Twitter, @OnlineCrsLady.