The Goat on the Rooftop

A young goat once managed to climb up onto the roof of the barn. As he stood there looking down, he saw a wolf who happened to be passing by. "Hey Wolf!" he shouted. "I can smell your stinking breath all the way up here!" The wolf paused, looked up at the little goat, but said nothing. "Didn't you hear me?" the kid shouted more loudly. "I CAN SMELL YOUR STINKING BREATH ALL THE WAY UP HERE." Still the wolf did not react. As the goat opened his mouth to bleat even more loudly, the wolf shouted back, "Enough already, little kid. It's not you who insults me, but the rooftop. If you really want to smell my breath, please, come on down!" The wolf waited for a moment and then, when the little goat did not come down, he snickered and continued on his way.

For my version, I wanted to make sure I included some actual insulting language by the goat; most versions of the fable do not include the actual insulting language. I also wanted to have the wolf say the "rooftop" was insulting him. The idea of a rooftop speaking insults is weird and funny. Of course, the wolf means that it is the kid's safe location on the rooftop that prompts his insults, but he expresses that idea with figurative language (another trademark feature of Aesop's fables), as if the rooftop could speak. Other versions have more practical locations for the little goat: on a haystack, peeping through a hole in the door, etc. But the rooftop goes back to the ancient Aesop, so I kept it.

I like the idea that the endomythium could function as a kind of proverbial statement that you could use in dialogue with an actual human being who is represented by the kid on the rooftop. If someone insults you because they can do so with impunity (for whatever reason), you can say back, "It's not you who insults me, but the rooftop." Such a saying doesn't make sense without the fable story, much like the proverbial "sour grapes," which also does not make sense unless you know the Aesop's fable about the fox and the grapes which are not, in fact, sour.

I won't invoke this many English versions every time, but I wanted to share a range here with my first fable to give people a sense of what goes on in the English Aesopic tradition. Many English authors (and these are just a few of them!) have retold the stories, each in their own way; I am just the latest in that very long tradition.

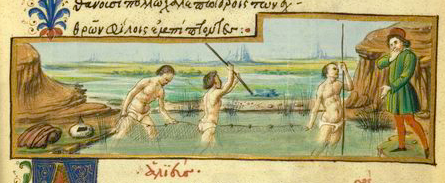

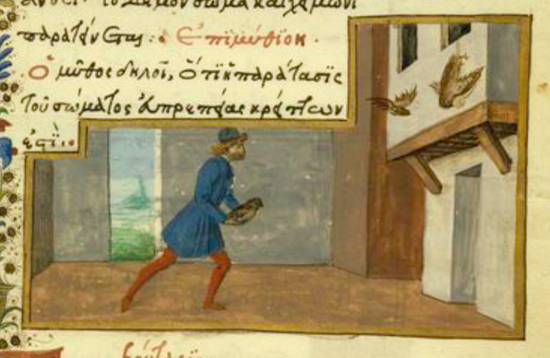

Here is the fable told very briefly in a popular 18th-century Latin textbook based on Aesop's fables which contains Latin fables with extremely literal English translations (click on the image for a larger view):

As you can see, no details about the insults, a boring endomythium (but at least there is an endomythium!), and a "moral of the story" which is pretty tedious too.

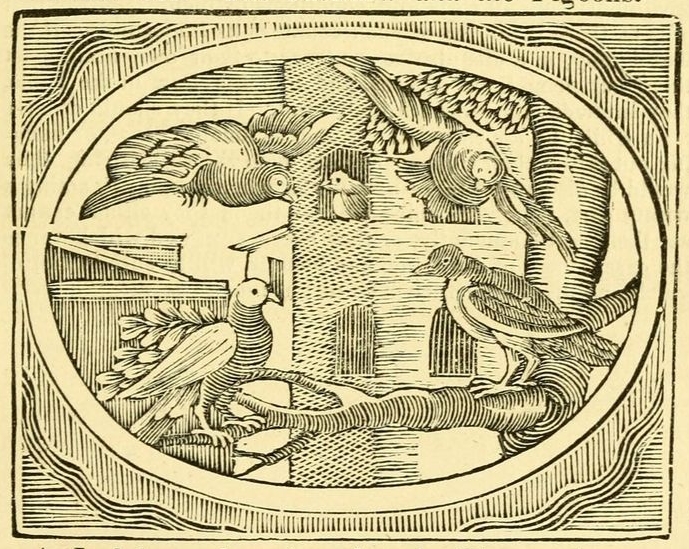

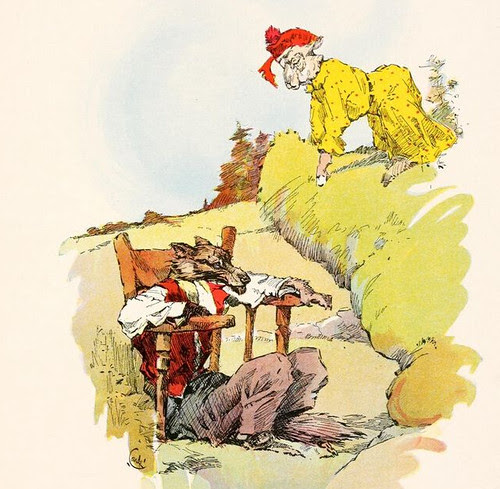

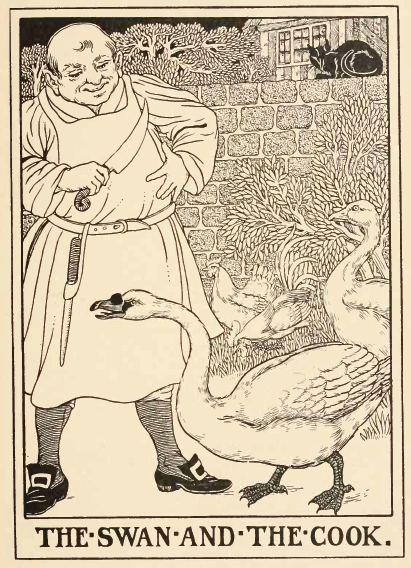

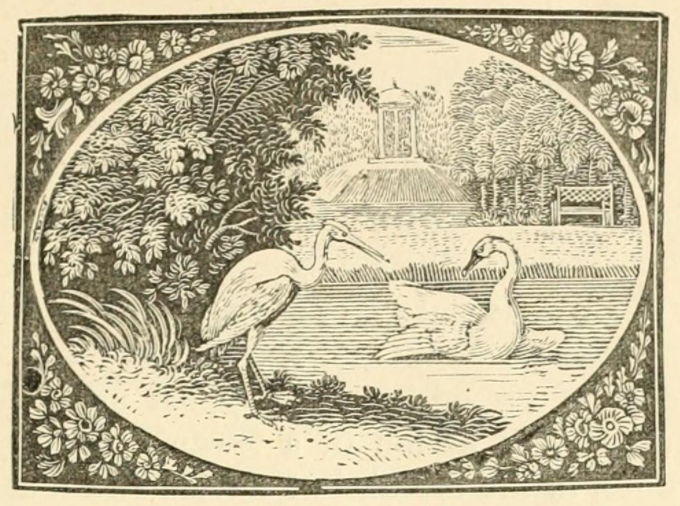

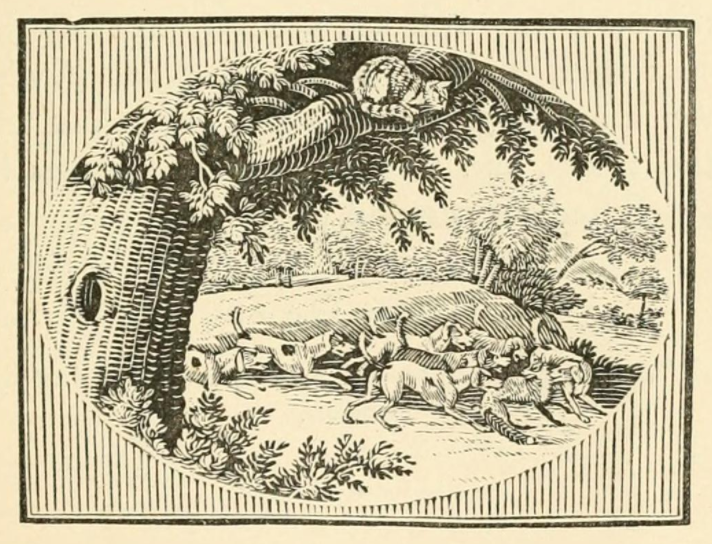

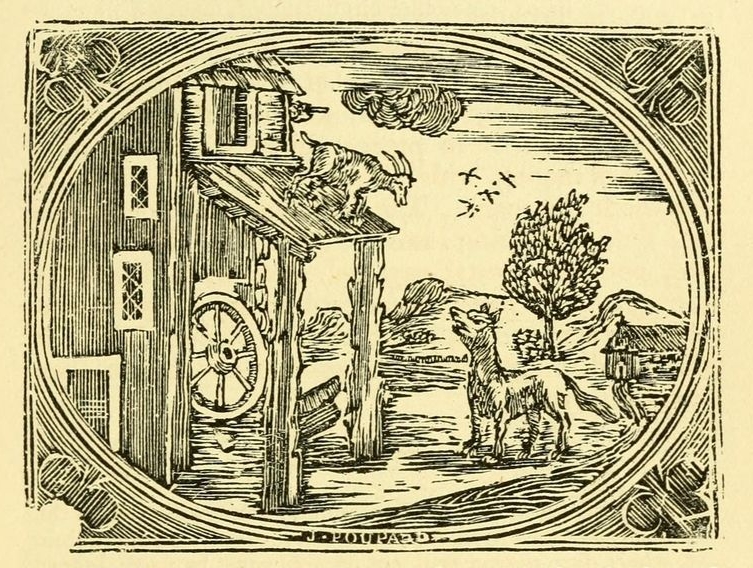

Much the same likewise in the popular Croxall's Aesop: A kid, being mounted upon the roof of a shed and seeing a wolf below, loaded him with all manner of reproaches. Upon which the wolf, looking up, replied, “Do not value yourself, vain creature, upon thinking you mortify me, for I look upon this ill language as not coming from you, but from the place which protects you.” This illustration is from an edition of Croxall:

Joseph Jacobs includes the goat's insults, but they are very pious insults, not really visceral. To his credit, Jacobs lets the wolf have the last word; no epimythium: A Kid was perched up on the top of a house, and looking down saw a Wolf passing under him. Immediately he began to revile and attack his enemy. "Murderer and thief," he cried, "what do you here near honest folks' houses? How dare you make an appearance where your vile deeds are known?" "Curse away, my young friend," said the Wolf. "It is easy to be brave from a safe distance."

This version from the anonymous Aesop for Children actually does have a good epimythium, with a nice proverbial style to it. If I were forced to include an epimythium, I would choose this one: A frisky young Kid had been left by the herdsman on the thatched roof of a sheep shelter to keep him out of harm's way. The Kid was browsing near the edge of the roof, when he spied a Wolf and began to jeer at him, making faces and abusing him to his heart's content. "I hear you," said the Wolf, "and I haven't the least grudge against you for what you say or do. When you are up there it is the roof that's talking, not you." Do not say anything at any time that you would not say at all times. (Note also that the author also wondered just how and why a goat would be on a rooftop and came up with an ingenious explanation of their own.)

My favorite English version is this one in verse by Herford! It doesn't include the kid's actual insults, but the wolf does invoke the hayloft in his reply: 'Tis the Loft laughs at me, not you. That would definitely make a good freestanding proverb of its own.

A Kid, safe in a hayloft high,

Laughed at a Wolf that happened by;

"Well," said the Wolf, "I must admit

Up there you have the best of it;

But let the Hayloft have its due,

'Tis the Loft laughs at me, not you;

If you don't think so, try your wit

Down here, and see who laughs at it!"

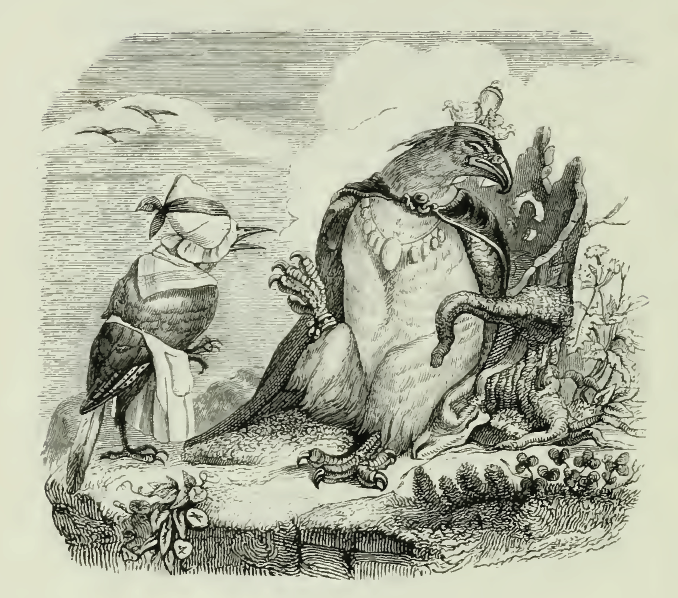

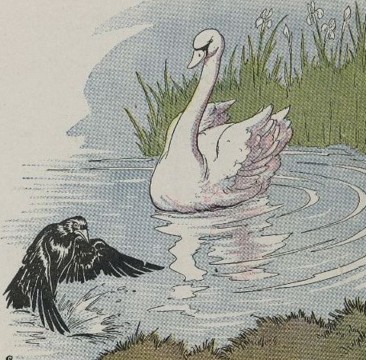

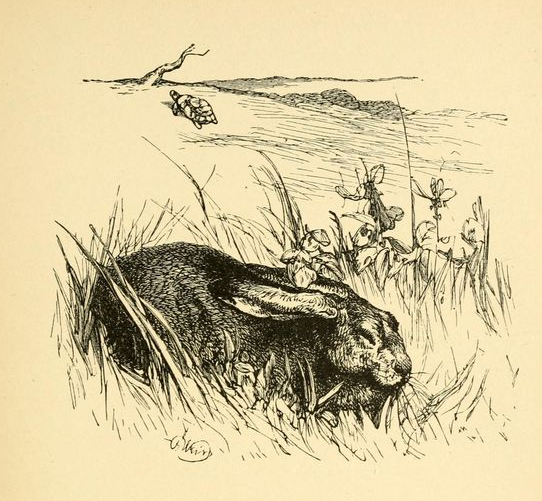

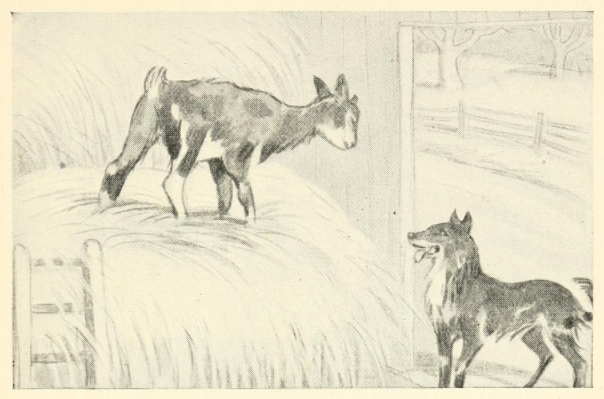

Here is Herford's illustration:

L'Estrange's English Aesop is always lively, and I like how his wolf also makes a threat at the end: As a Wolfe was passing by a Poor Country Cottage, a Kid spy'd him through a Peeping-Hole in the Door, and sent a Hundred Curses along with him. Sirrah (says the Wolfe) if I had ye out of your Castle, I'd make ye give Better Language. The Moral. A Coward in his Castle makes a Great Deal more Bluster then a Man of Honour. (You can also read L'Estrange's longer reflexion on the fable too; as always with L'Estrange, it's fun reading.)

Click here for more illustrations and English versions of this fable, and for more "favorite fables" at this blog, see the Aesopica label. You can find out more about this retelling project, see this post: Favorite Aesop's Fables.